Olive cultivation is a pillar of the Apulian culture and economy, but despite the importance of the plant, little is known about its origin or the time when it became the dominant cultivation in the region.

The project aims to create a comprehensive study, that includes evidence from different records, to outline of the history of the olive plant in Apulia from Prehistory to the Middle Age.

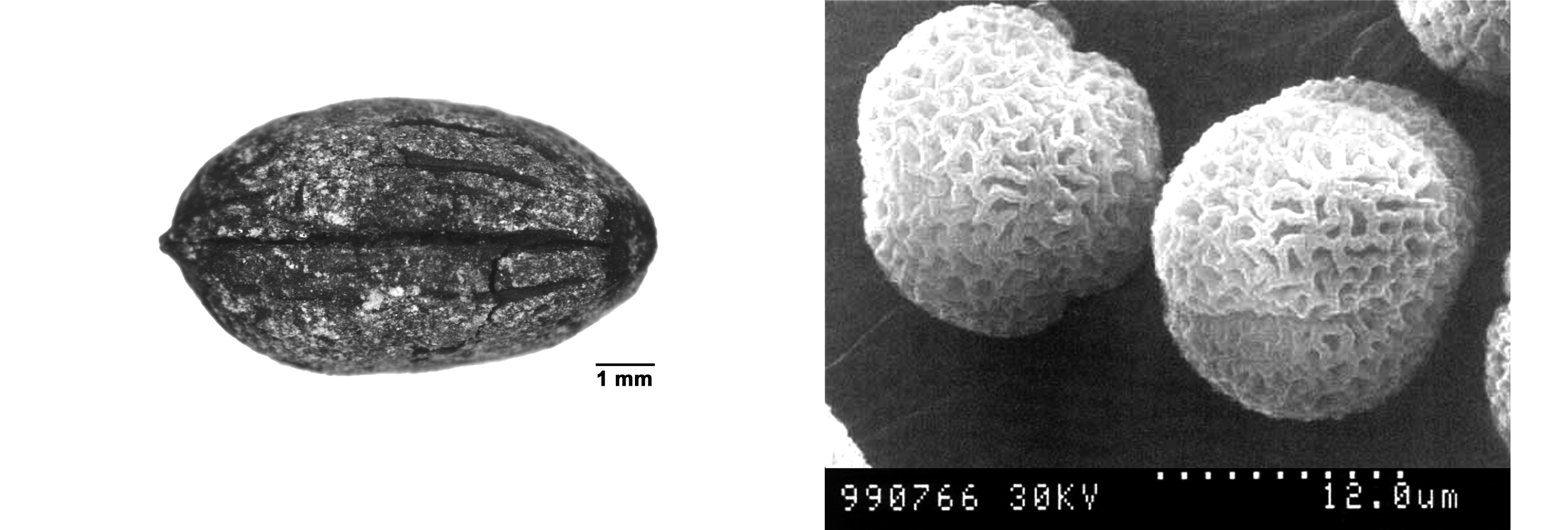

The primary source of information considered in the study were olive, olive presses and furnaces for the production of olive amphorae found in archaeological sites.

The survey also included pollen sequences from natural records and written documents dealing with the allotment of olive orchards. A major achievement of the project is the valorization of a product, such as the olive oil, which has a cultural identity that is deeply related to the Apulian agro-ecological system.

Workshop "Olivo e Olio d'olivo in Puglia"

Lecce, 10 dicembre 2018

Scarica la presentazione del Progetto nell'ambito del Workshop

Sample map

Abbreviations:

A.I.:

Archaeological Installation/Installazione

Archeologica Arch:

Archaic/Età Arcaica B.A.: Bronze

Age/Età del Bronzo Byz.:

Bizantine/Età Bizantina CH.:

Charcoal/Carbone

Abulafia D (1977) The Two Italies. Economic Relations Between the Norman Kingdom of Sicily and the Northern Communes. Cambridge University Press

Accorsi CA, Mazzanti M, Mercuri AM (1995) Le analisi palinologiche nel sito mesolitico/neolitico antico medio di Terragne (96 m slm, 40° 24’N 17° 38’E, Manduria-Taranto; Sud Italia). In: Gorgoglione MA, Di Lernia S, Fiorentino G (eds) L’insediamento preistorico di Terragne (Manduria-Taranto), nuovi dati sul processo di neolitizzazione del sudest italiano. CRSEC, Manduria, pp 185–198

Alessio A (2001) Grottaglie (Taranto), Oliovitolo, F. 202 I N.E. Taras 21:102–103

Amelli A (1903) Quaternus de excadenciis et revocatis Capitanatae de mandato imperialis maiestatis Frederici secundi. Typis archicoenobii Montis Casini, Montecassino

Andreassi G (2006) L’attività archeologica in Puglia nel 2005. In: Atti del Convegno della Magna Grecia 45. ISAMG. Taranto, pp 605–625

Antonacci San Paolo E (1995) Ricerche archeoambientali nella Daunia antica. Paesaggio vegetale e allevamento tra documentazione archeologico-letteraria ed analisi dei reperti naturalistici. In: Quilici L, Quilici Gigli S (eds) Atlante tematico di topografia Supp l. L’erma Di Bretschneider, Rome, pp 73–102

Aprile G, Fiorentino G (2018) L’analisi antracologica delle terre di rogo per la comprensione del rituale incineratorio: i tumuli eneolitici di Salve (LE). In: Atti della 47ima riunione dell’Istituto di Preistoria e Protostoria, Ostuni 9-13 ottobre 2012

Arthur P, Fiorentino G, Grasso A (2012) Roads to recovery: an investigation of early medieval agrarian strategies in Byzantine Italy in and around the eighth century. Antiquity 86:444–455

Arthur P, Fiorentino G, Imperiale ML (2008) L’insediamento in Località Scorpo (Supersano, LE) nel VIIVIII secolo d.C. La scoperta di un paesaggio di età altomedievale. Archeol Mediev 35:234–236

Caggese R. (1922) Roberto d’Angiò e i suoi tempi. Vol. I. Bemporad Editori, Firenze

Carabellese F (1899) Le pergamene della Cattedrale di Terlizzi (971-1300), CDB III. Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Caracuta V, Fiorentino G (2017) Plant Rituals and Fuel in Roman Cemeteries of Apulia (SE Italy). In: Livarda A, Madgwick R, Riera Mora S (eds) The bioarchaeology of ritual and religion. Oxbow Books, Oxford & Philadelphia, pp 58–68

Caracuta V, Fiorentino G (2013) Riti funerari e paesaggio vegetale nel territorio di Ausculum: il contributo dell’analisi archeobotanica per lo studio della necropoli di Via Giuseppe Ciotta. In: Corrente M (ed) Lo spreco necessario, il lusso nelle tombe di Ascoli Satriano. Claudio Grenzi, Foggia, pp 160–164

Caracuta V, Fiorentino G (2009) L’analisi archeobotanica nell’insediamento di Faragola (FG): il paesaggio vegetale tra spinte antropiche e caratteristiche ambientali tra Tardoantico e Altomedioevo. V Congr Naz di Archeol Mediev (Foggia, Manfredonia, 30 settembre-1 ottobre 2009) 371–377

Caracuta V, Fiorentino G (2012) Ambiente e strategie produttive nei siti di San Lorenzo in Carminiano e Pantano (FG) tra XIII e XIV secolo. In: Favia P, Houben H, Tomaspooeg K (eds) Federico II e i Cavalieri Teutonici in Capitanata. Recenti ricerche storiche e archeologiche., Congedo ed. Galatina, pp 317–332

Caroli I, Caldara M (2007) Vegetation history of Lago Battaglia ( eastern Gargano coast , Apulia , Italy ) during the middle-late Holocene. Veg Hist Archaeobot 16:317–327. doi: 10.1007/s00334-006-0045-y

Casucci A (2007) L’insediamento rurale di Malano nel territorio di Acquaviva delle Fonti. Università degli Studi di Bari

Ciancio A, Small A (1990) Gravina in Puglia (BARI), Botromagno. Taras 10:360–361

Ciaraldi M (1997) Oria, Monte Papalucio: i resti vegetali delle offerte di età arcaica e Ellenistica. In: D’Andria F (ed) Metodologie di catalogazione dei beni archeologici. Beni archeologici. Conoscenza e tecnologie, Quaderno I.1. Lecce/Bari. Forum, Martano, pp 211–228

Colaianni GP (2008a) Analisi archeobotaniche nel Salento tra IX sec. a.C. e IV sec. a.C.: ricostruzioni funzionali e implicazioni paleovegetazionali. Università del Salento-Lecce.

Colaianni GP (2008b) Problematiche interpretative del record archeobotanico della tomba di via Perrella, Alezio (LE). In: D’Andria F, De Grossi J, Fiorentino G (eds) Uomini, piante e animali nella dimensione del sacro. Edipuglia, Bari, pp 39–45

Colaianni GP (2012a) Storia del paesaggio di Lecce tra ricostruzione archeobotanica e proposta museale. In: D’Andria F, Mannino C (eds) Gli allievi raccontano. Atti dell’incontro di studio per i trent’anni della Scuola di Specializzazione in Beni Archeologici “D. Adamesteanu”., Congedo Ed. Galatina, pp 285–292

Colaianni GP (2012b) Sviluppo di metodologie finalizzate alla ricostruzione del paesaggio vegetale urbano e periurbano di Lecce tra il IV sec. a.C. e il XVII sec. d.C. e relativo progetto di comunicazione dei dati acquisiti. Univsersità del Salento

Combourieu-Nebout N, Peyron O, Bout-Roumazeilles V, et al (2013) Holocene vegetation and climate changes in the central Mediterranean inferred from a high-resolution marine pollen record (Adriatic Sea). Clim Past 9:2023–2042. doi: 10.5194/cp-9-2023-2013

Coniglio G (1975) Le pergamene di Conversano, I (901-1265)., CDP XX. Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Corrente M (2012) La natura costruita. Identità naturale e storica della villa di Casalene., ARA Edizio. Roma

Corrente M, Albanesi C, Distasi V, et al (2008a) Prima e dopo Roma. Sostrati formativi e profilo culturale della Daunia alla luce delle recenti attività di scavo della Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Puglia. In: Gravina A (ed) Atti del 28 Convegno Nazionale sulla Preistoria–Protostoria–Storia della Daunia. ArcheoClub, San Severo, pp 375–404

Corrente M, Battiante M, Ceci L, et al (2008b) Le diverse esigenze: paesaggio rurale, archeologia preventiva e fattorie del vento. In: Gravina A (ed) Atti del 28 Convegno Nazionale sulla Preistoria–Protostoria–Storia della Daunia. ArcheoClub, San Severo, pp 341–374

Corsi P (1974) Le pergamene dell’Archivio Capitolare di San Severo (secoli XII-XV).

D’Andria F (2004) Il sottosuolo come risorsa di conoscenza e sviluppo. Archeologia urbana, metodi e prospettive della ricerca. In: De Stefano M (ed) Lecce. Riqualificazione e valorizzazione ambientale, architettonica, e archeologica del centro storico., De Luca. Roma, pp 44–67

D’Oronzo C (2012) Strutture di combustione e contesti archeologici: indagine archeobotanica e definizione del protocollo d’intervento. Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore Milano

D’Oronzo C, Fiorentino G (2017) Lo studio dei resti vegetali provenienti dai livelli dell’Età del Bronzo del Castello di Mola di Bari. In: Atti della XLVII Riunione Scientifica Preistoria e Protostoria della Puglia-. pp 945–948

D’Oronzo C, Fiorentino G (2008) L’analisi archeobotanica condotta nel sito neolitico di Foggia in località Monte Calvello. In: Atti del 28 Convegno sulla Preistoria–Protostoria e Storia della Daunia. pp 441–448

Dalena P (2010) Olivo e olio. In: Dalena P, Carnevale P, Di Muro A, La Manna F (eds) Mezzogior- no rurale. Olio, vino e cereali nel Medioevo. pp 15–121

De Capua D. (1987) I capitoli bitontini sono. In: Palo del Colle DA (ed) Libro rosso dell’Università di Bitonto (1265-1559). Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari, pp 878–984

De Juliis EM (1985) Un quindicennio di ricerche archeologiche in Puglia: 1970-1984. Parte II: 1978-84. Taras 5:177–228

De Leo A (1940) Codice Diplomatico Brindisino I (492-1299). Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Di Rita F, Magri D (2009) Holocene drought , deforestation and evergreen vegetation development in the central Mediterranean : a 5500 year record from Lago Alimini Piccolo , Apulia , southeast Italy. The Holocene 19:295–306

Di Rita F, Simone O, Caldara M, et al (2011) Holocene environmental changes in the coastal Tavoliere Plain ( Apulia , southern Italy ): A multiproxy approach. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 310:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.06.012

Federici V (1926) Chronicon Vulturnense del Monaco Giovanni. Vol. I. Tipografia del Senato, Roma

Filangieri R (1926) Le pergamene di Barletta del Reale Archivio di Napoli (1075-1379), CDB X. Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Filangieri R (1954) I registri della Cancelleria angioina, ricostruiti da Riccardo Filangieri con la collaborazione degli archivisti napoletani. Vol. IV. Napoli

Fiorentino G (1999a) Caratteristiche della vegetazione e abitudini alimentari durante la preistoria. In: Mastronuzzi C, Marzo A (eds) Le isole Cheradi, fra natura, leggenda e storia. Fondazione Ammiraglio Michelangio, pp 69–78

Fiorentino G (1995a) Analisi dei macroresti vegetali. In: Gorgoglione M, Di Lernia S, Fiorentino G (eds) L’insediamento preistorico di Terragne (Manduria - Taranto), nuovi dati sul processo di neolitizzazione del sudest italiano. C.R.S.E.C., Manduria, pp 171–184

Fiorentino G (1998) Le risorse vegetali. In: Cinquepalmi A, Radina F (eds) Documenti dell’età del Bronzo. Ricerche lungo il versante adriatico pugliese. Schena, Foggia, pp 211–221

Fiorentino G (1995b) Primi dati archeobotanici nell’insediamento dell’età del Bronzo di Monopoli e Piazza Palmieri. Taras 15:335–373

Fiorentino G (1999b) Ricerche archeobotaniche e paleoambientali. In: Arthur P (ed) Da Apigliano a Martano. Tre anni di archeologia medievale (1997-1999)., Congedo. Galatina, pp 54–56

Fiorentino G, D’Oronzo C (2012) Analisi dei macroresti vegetali: strategie agronomiche, alimentazione e caratteristiche del paleoambiente a Coppa Nevigata nel corso dell’età del bronzo. In: Cazzella A, Moscoloni M, Recchia G (eds) Coppa Nevigata e l’area umida alla foce del Candelaro durante l’età del Bronzo, Claudio Gr. Foggia, pp 327–337

Grasso A, Fiorentino G, Stranieri G (2012) Brick in the wall: an archaeobotanical approach to the analysis of dry stone structures (Puglia-Italy). SAGVNTVM extra 13:209–216

Grasso AM, Fiorentino G Ricerche archeobotaniche nel Castello Carlo V di Lecce. In: Arthur P, Veter B (eds) Castrum Licii- La Torre Angioina.

Heim J (1995) Il paesaggio vegetativo. In: Mertens J (ed) Herdonia. Scoperta di una città. Institut historique belge de Rome, Rome, pp 312–324

Ingrosso A (2004) Il Libro Rosso di Gallipoli (Registro dei Privilegi). Congedo Editore, Galatina

Leccisotti T (1949) Le relazioni tra Montecassino e Tremiti e i possedimenti cassinesi a Foggia e Lucera. Benedictina 3:214

Leccisotti T (1937) Le colonie cassinesi in Capitanata, I, Lesina (sec. VIII-XI).

Leccisotti T (1957) Le colonie cassinesi in Capitanata, IV, Troia. Miscellanea Cassinese 29, Montecassino

Lentjes D (2011) Risultati delle analisi del materiale botanico recuperato nelle campagne di scavo. In: Burgers G-J, Crielaard JP (eds) Greci e indigeni a l’Amastuola. Mottola. Stampa Sud, Foggia, pp 93–104

Lentjes D (2010) La fioritura dell’ambiente. I risultati preliminari del recupero dei resti archeobotanici a Muro Tenente. In: Burgers G-J, Napolitano C (eds) L’insediamento messapico di Muro Tenente, Scavi e ricerche 1998-2009. Reale Istituto Neerlandese, Rome, pp 53–60

Manacorda D (1990) Le fornaci di Visellio a Brindisi. Primi risultati dello scavo. Vetera Christ 27:375–415

Marcantonio M (2001) Note sul territorio di Alberona in provincia di Foggia. In: Quilici L, Quilici Gigli S (eds) Urbanizzazione delle Campagne dell’Italia antica. Atlante Tematico di Topografia Antica 10. L’Erma di Bretschneider, Roma, pp 243–257

Marchesini M, Marvelli S, Bandini Mazzanti M, Accorsi CA (1995) Ricerche archeoambientali nella Daunia antica. In: Quilici L, Quilici Gigli S (eds) Atlante tematico di topografia Supp l. L’erma Di Bretschneider, Rome, pp 103–111

Marsicano L (1115) Cronaca di Montecassino vol. III, 2001st edn. Jaka books, Milano

Martin JM (1993) La Pouille du VIe au XIIe siècle. Vol. I, Ecole fran. Roma

Martin JM (1976) Les Chartes de Troia. Edition et étude critique des plus anciens documents conservés à l’Archivio Capitolare (1024-1266)., CBP XXI. Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Mommsen T (1883) Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IX, 665. Berlin Academy, Berlin

Nitti de Vito F (1900) Le pergamene di S. Nicola di Bari. Periodo greco (939-1071), CDB IV. Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Nitti de Vito F (1902) Le pergamene di S. Nicola di Bari. Periodo Normanno (1075-1194).

Nitti de Vito F (1906) Le pergamene di S. Nicola di Bari. Periodo svevo (1195-1266)., CDB VI. Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Nitti de Vito F (1914) Le pergamene di Barletta, Archivio Capitolare (897-1285). Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Nitto De Rossi GB, Nitto de Vito F (1897) Le pergamene del Duomo di Bari (952-1264)., CDB I. Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, Bari

Pagliara C (1968) Bolli anforari inediti da Felline (Prov. Lecce). Stud Cl Orient 17:227–231

Palazzo P (1994a) I siti artigianali nel territorio brindisino. In: MArangio C, Nitti A (eds) Scritti di antichità in memoria di Benita Sciarra Bardaro, Schena. Fasano, pp 53–60

Palazzo P (1994b) Località Marmorelle: le fornaci e i reperti anforari. In: Pani M (ed) Epigrafia e territorio, politica e società: temi di antichità romane III. Edipuglia, Bari, pp 201–225

Parisi V, Marchetti CM, Lollino W, et al (2018) Saturo, Ta, Acropoli: la frequentazione tra VIII secolo aC ed età romanatardo-imperiale, campagne di scavo 2014-17. Sci dell’Antichità 24:231–293

Pasquino silvia (2015) Analisi archeobotaniche del sto pluristratificato di Castro, Località Capanne. Università del Salento-Lecce, Italy.

Pastore M (1964) Le pergamene della Curia e del Capitolo di Nardò. Vol.5. Centro Studi Salentini, Lecce

Petrucci A (1961) Codice diplomatico del Monastero benedettino di S. Maria di Tremiti: (1005-1237). Istituto storico italiano per il Medio Evo, Spoleto

Primavera M (2008) I dati archobotanici della sepoltura neolitica di Carpignano (LE): alcune considerazioni. In: D’Andria F, De Grossi Mazzorin J, Fiorentino G (eds) Uomini, piante e animali nella dimensione del sacro., Edipuglia. Bari, pp 193–200

Primavera M (2011) Il combustibile delle attività metallurgiche nelle forge di Lecce tardo-antica: caratteristiche della vegetazione e sfruttamento dell’ambiente. In: Giardino C (ed) Archeometallurgia: dalla Conoscenza alla Fruizione. Edipuglia, Bari, pp 321–331

Primavera M, D’Oronzo C, Muntoni IM, et al (2017) Environment, crops and harvesting strategies during the II millennium BC: Resilience and adaptation in socio-economic systems of Bronze Age communities in Apulia (SE Italy). Quat Int 436:83–95

Primavera M, Fiorentino G (2012) I resti vegetali delle postierle B e C. In: fortificazioni della media età del Bronzo. Strutture, contesti, materiali. Scarano, G., Foggia, pp 353–358

Primavera M, Fiorentino G (2011) Archaeobotany as an In site/Off site tool for palaeoenvironmental research at Pulo di _Molfetta (Puglia, SE Italy). In: Turbati-Memmi E (ed) Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium on Archaeometry. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 441–426

Prologo A (1877) Le carte che si conservano nello Archivio del capitolo metropolitano della città di Trani dal ix secolo fino all’anno 1266. Barletta

Renault-Miskovsky J, Bui-Thi-Mai Y (1997) Étude pollinique du site néolithique de Scamuso (Bari, Italie). In: Biancofiore F, Coppola D (eds) Scamuso. Per la storia delle comunità umane tra il VI ed il III millennio nel basso adriatico. Dipartimento di Storia dell’Universita’di Roma" Tor Vergata" Paletnologia, Rome, pp 185–197

Rivera Magos V (2013) Olivi e olio nel medioevo pugliese. Produzione e commercio tra XI e XIV secolo. In: Violante F (ed) De bono oleo claro de olivo extracto. La cultura dell’olio nella Puglia medievale., Caratterim. Bari, pp 26–49

Robinson G (1928) Taranto. History and Cartulary of the Greek Monastery of St. Elias and nd St. Anastasius of Carbone. Orient Christ 15:

Solinas F (2008) Il Megaron delle meraviglie: culti ctoni ed offerte vegetali nell’area santuariale di Vaste-Piazza Dante (LE) nel corso del IV-III sec. a.C. In: D’Andria F, De Grossi Mazzorin J, Fiorentino G (eds) Uomini, piante e animali nella dimensione del sacro. Edipuglia, Bari, pp 235–243

Stellati A (2014) Le dinamiche di gestione delle risorse vegetali ad Egnazia (BR) tra età Romana e Medioevo: un approccio integrato. Università degli Studi di Bari.

Valchera A, Zampolini Faustini S (1997) Documenti per una carta archeologica de/la Puglia meridionale. In: Guaitoli M (ed) Metodologie di Catalogazione dei Beni archeologici I-2. Congedo Editore, Galatina, pp 103–158

Volpe G (1990) La Daunia nell’età della romanizzazione. Edipuglia, Bari

Volpe G (1996) Contadini, pastori e mercanti nell’Apulia tardoantica. Edipuglia, Bari

Classical authors

Horatio. Odes and Epodes. Translated by Rudd. Loeb Classical Library No. 33. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Varro. On Agriculture. Translated by Hooper. Loeb Classical Library No. 283

Pliny. Natural History. Translated by Rackham, Jones, Eichholz. Loeb Classical Library No. 352. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Cassiodorus.Variae. Translated by Barnish. Oxford University Press.

Strabo. Geography, book VI. Translated by Jones. Loeb Classical Library No. 182. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

The project ELAION - Enhancing the history of Apulian olive oil to promote a local brand aims to enhance the Apulian olive tree as a symbol of the historical memory of this land and to propose to the consumers a taste of the ancient tradition of the local olive oil. The project ELAION was financed by European Social Fund (FSE) and Apulian Regional Council, on the measure “Future In Research”, 2015-2018 (Grant Number 5ACGSJG4).

The project was carried out by Dr Valentina Caracuta and hosted by the Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Palaeoecology of the Salento University.

AddressLaboratorio di Archeobotanica e Paleoecologia

Dipartimento di Beni Archeologici

Via Birago 64, 73100 Lecce

Phone +39 0832 291111

Email projectelaion@gmail.com